Different types of Nomadic Tents in Turkey

November 18, 2020

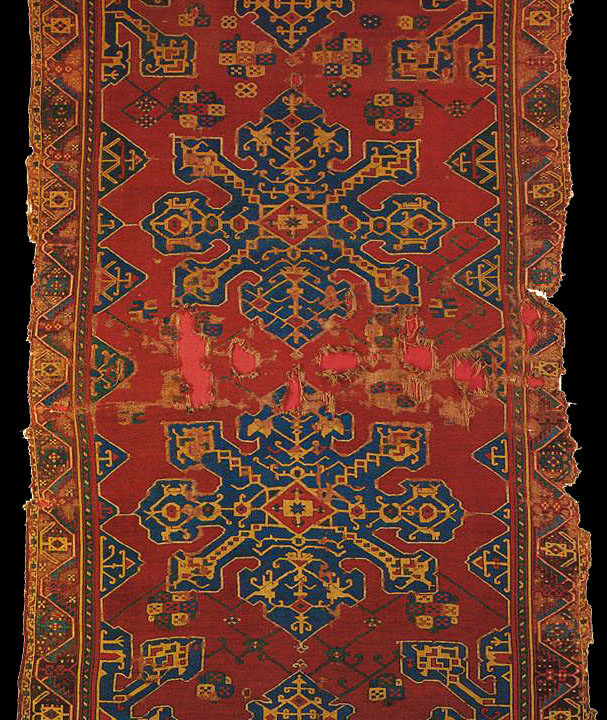

Handwoven Carpets of Turkey -1 Eastern Anatolia

November 19, 2020The nomads in Turkey have based their culture and traditions mostly on animal husbandry and textile production. The nomadic textiles are as famous as the sheep and goats that they feed. Durable, elaborately designed, and functional, these textile products were not only appreciated by Anatolian nomad communities themselves but by sedentary people, too, even in urban environments.

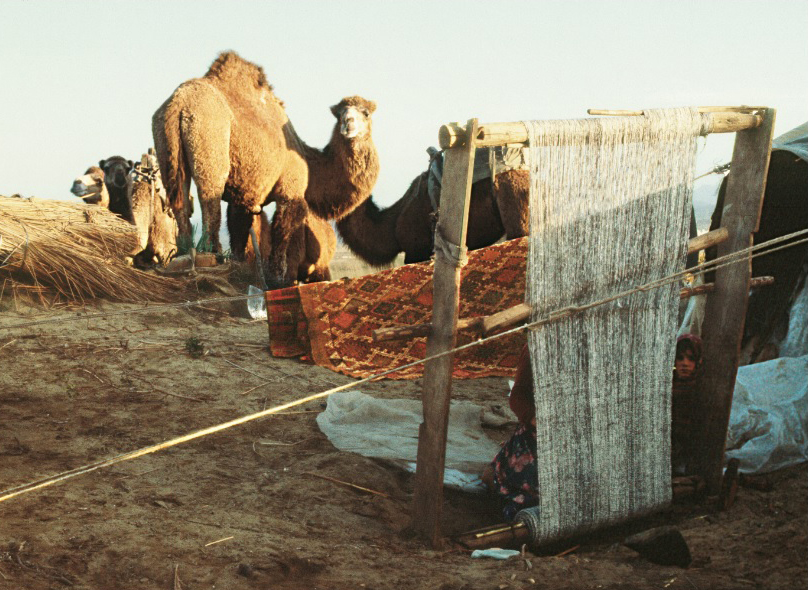

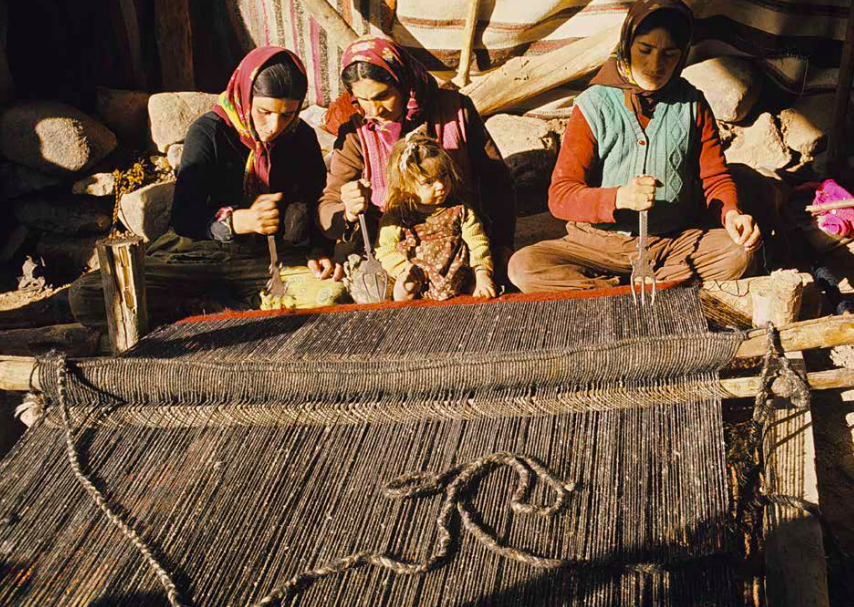

Sacikara Turkmen Encampment, a new weaving is set up on the loom, Kahramanmarash, Eastern Turkey, 1980, photo courtesy, Josephine Powell, Suna Kıraç Foundation

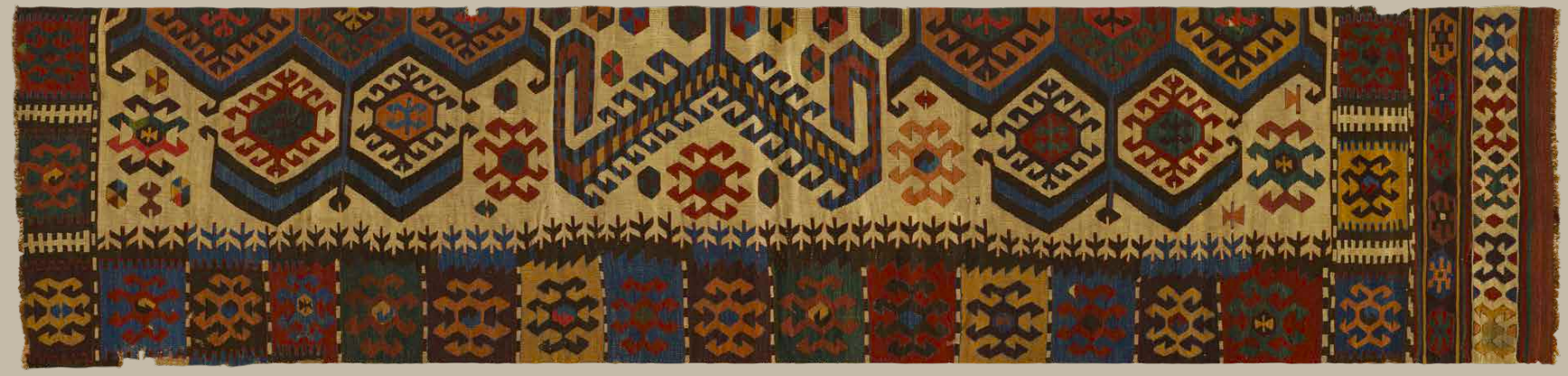

A very elaborate nomadic kilim, mid-19th century, Cental Turkey Megalli Collection Washington DC. Textile Museum

The textiles are generally produced by women in the nomadic society of Turkey. The textile production of nomads includes only one step by men, which is shearing the animals. Nomads shear their animals once a year. The sheep wool and the goat hair are separated according to their colors and stored in this way.

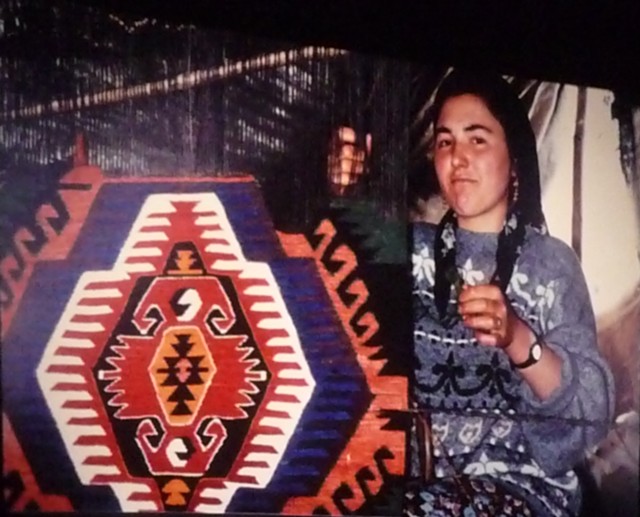

Sachikara Turkmen, tribeswoman, with the kilims she wove, Kahramanmarash, Eastern Turkey, photo courtesy Josephine Powell, Suna Kıraç Foundation

Sarıkeçili Turkmen tribeswoman showing the kilim she wove, covering the nomadic sacks in the tent. kdağ Pasture, Fethiye, South-Western Turkey, 1980s, photo courtesy Josephine Powell, Suma Kıraç Foundation

Just after the wool is shorn, the first thing to do is to expose the shorn fleece to the sunlight. The sweat and the urine of the animal will evaporate and the wool will be ready to be washed. One fleece obtained from one sheep weighs approximately two or three kilos when dirty. After being washed and dried, the wool will lose half of its weight and will be around one or one and a half kilograms. So we can say that the dirty wool can keep as much dirt, dust, and humidity as its weight.

Beritan Kudish tribeswoman shears the wool. Mus, Eastern Turkey

The fleeces are exposed to the sunlight, the sweat and urine of the sheep dry out. Beritan encampment Eastern Turkey

The wool fleeces are washed by women after being completely dried out in the sunshine. The best way to wash is to beat the wetted wool continuously with long and heavy sticks. There is no need to use any artificial soap or detergent agent. The alkaline property of the dried sweat and urine begins the saponification reaction and the wool is bubbling up. The beating also drives out the spiky burrs and the impurities. After the washing and rinsing in cold stream water, the wool is laid out on the grass in the sunshine and dried.

The wool fleece is washed by beating it with sticks

After this stage, the wool is combed by special combs and all of the fibers within the wool are brought parallel to each other. This will enable the wool to be spun easily and in a uniform thickness.

Antique Anatolian Turkmen wool comb. late 19th century Women comb the wool in Artvin, North-Eastern Turkey

If there is a rush for the spinning process, the Anatolian nomads will use a big bow made of sheep gut and a wooden bended branch to make the fleece fluffy enough to be spun. They put some yarn onto the gut string of the bow and make it vibrate so that the fleece will open up by the effect of the vibration. The wool yarn spun after this process would be less uniform by this way.

Processing wool with a bow

The spinning requires continuous attention and handwork to make a uniform yarn. In each gesture, the fingers should pull the same amount of fibers from the combed wool roll that is called “tops” and let the spindle turns the fibers into the string or yarn. Generally, nomads of Turkey use the drop spindle so that they can move, walk, or do other activities while spinning.

Sinanlı Kurdish tribeswoman spinning wool, 1980s Malatya, Eastern Turkey, photo courtesy Josephine Powell. Suna Kıraç Foundation

The yarns are spun with many or few turns so the yarn would be loosely spun or tightly spun. This property of the yarn is decided according to the place that it will be used. Pile carpet yarns are loosely spun, the warp yarns are tightly spun, and the weft and kilim yarns are spun medium tightly. The warping yarns are unified as two layers and those layers are always twisted to in opposite directions so the warp will be durable during weaving on the loom. From time to time the combed wool or fluffed fleece is wetted just a bit to obtain some lubrication effect while spinning extremely fine yarn.

After the yarns are prepared, the dyeing process is begun, with herbal dyestuffs and yarns boiled together until reaching the desired color. Mordants, which are metallic salt-type color fixers of wool yarns are used, too, to fortify the color or create a distinct hue. The yarns are rinsed and dried. After this process, the weaving operation may begin.

Red dyeing process in Örselli village, Manisa, Western Turkey, 2007

Natural-Dyed yarns are dried, Örselli village Manisa, Western Turkey, 2000s

A Karakoyunlu Turkmen girl weaves a kilim, Çayır Pasture, Beyşehir, Konya, Central TUrkey photo courtesy, Josephine Powell, Suna Kıraç Foundation

For the goat hair, almost the same process is followed except the washing of the shorn hair and dyeing. The hair is not washed, but the textile is washed after being woven. Also, the goat hair is generally not dyed but is used with its natural color.

A local festival of Turkmens who shear hair from the goats, Seferihisar İzmir, Western Turkey

Spinning goat hair Gümüşhane, Eastern Turkey

Spinning goat hair Gümüşhane, Eastern Turkey

A Kurdish nomadic family weaves a goat hair textile in front of the loom, Pazarcık, Kahramanmarash, Eastern Turkey, photo courtesy Josephine Powell, Suna Kıraç Foundation

Some other fibers are also used by nomads of Turkey according to the thickness and functionality of the textile. Horse mane hair can be used in very coarse weavings as a structure fortifier. Angora, the hair of the Angora goat and which is rare, comma is used to embellish the textiles or to produce very fine and delicate textiles. Hemp is also used from time to time if found abundantly. Their processing is more or less similar to the above operations but requires experience and knowledge.

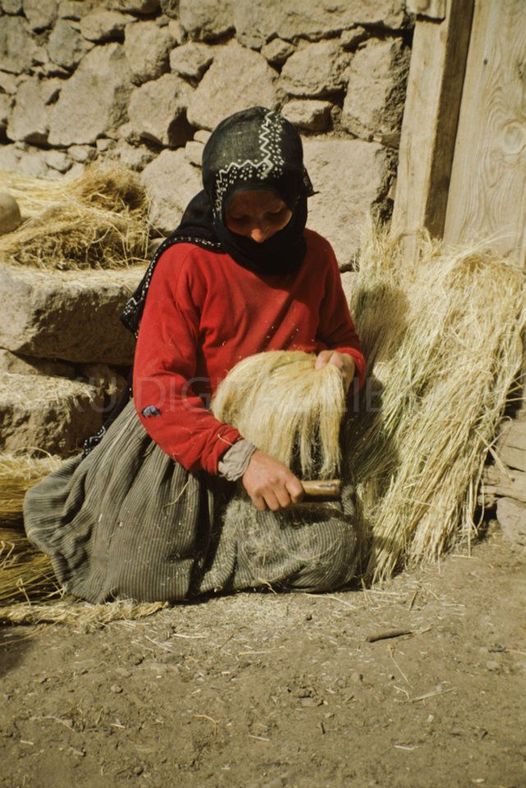

Anatolian village woman combing hemp to be spun and woven. Central Turkey, photo courtesy Josephine Powell, Suna Kıraç Foundation